The Sikhs & The Gurmata

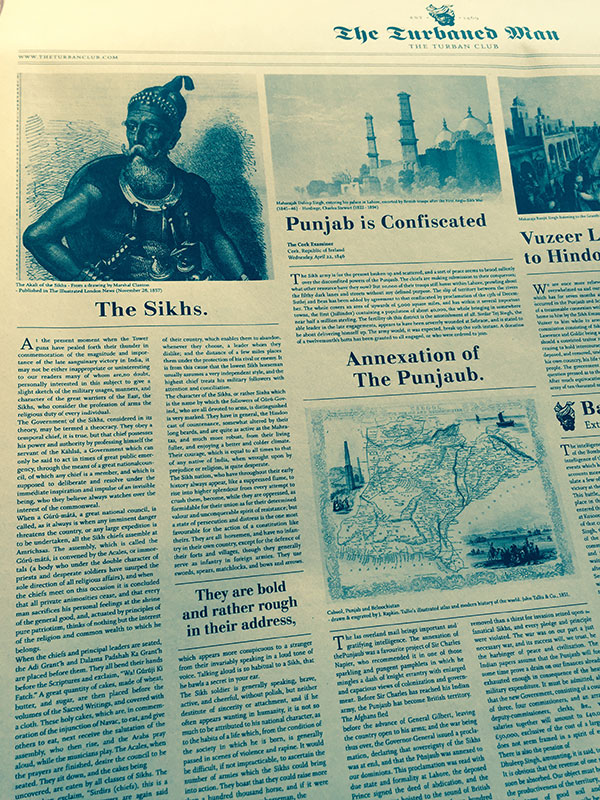

At the present moment when the Tower guns have pealed forth their thunder in commemoration of the magnitude and importance of the late sanguinary victory in India, it may not be either inappropriate or uninteresting to our readers ─many of whom are, no doubt, personally interested in this subject─ to give a slight sketch of the military usages, manners, and character of the great warriors of the East, the Sikhs, who consider the profession of arms the religious duty of every individual.

The Government of the Sikhs, considered in its theory, may be termed a theocracy. They obey a temporal chief, it is true, but that chief possesses his power and authority by professing himself the servant of the Khálsá,

a Government which can only be said to act in times of great public emergency, through the means of a great national council, of which any chief is a member, and which is supposed to deliberate and resolve under the immediate inspiration and impulse of an invisible being, who they believe always watches over the interest of the commonweal.

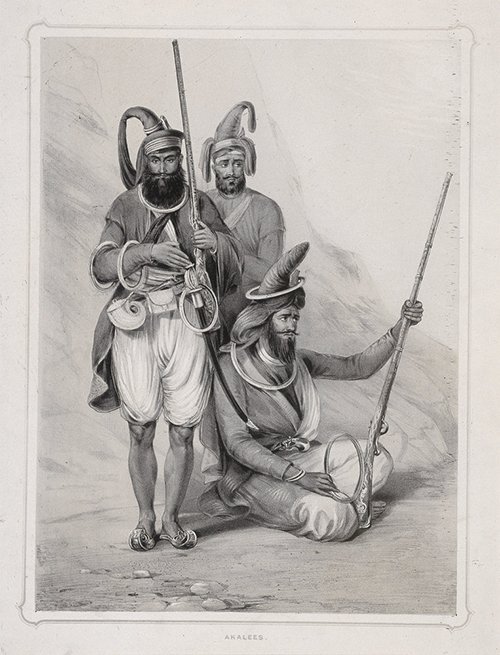

AkaleesBy Emily Eden, 1844.

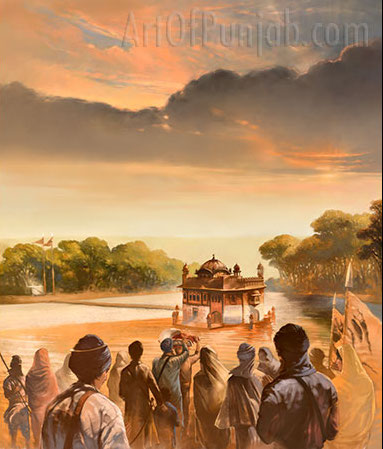

When a Gúrú-mátá, a great national council, is called, as it always is when any imminent danger threatens the country, or any large expedition is to be undertaken, all the Sikh chiefs assemble at Amritsar. The assembly, which is called the Gúrú-mátá, is convened by the Acales, or immortals (a body who under the double character of priests and desperate soldiers have usurped the sole direction of all religious affairs).

When the chiefs meet on this occasion it is concluded that all private animosities cease, and that every man sacrifices his personal feelings at the shrine of the general good, and, actuated by principles of pure patriotism, thinks of nothing but the interest of the religion and common wealth to which he belongs.

When the chiefs and principal leaders are seated, the Adi Grant’h and Dalama Padshah Ka Grant’h [sic] are placed before them. They all bend their hands before the Scriptures and exclaim, “Wa! Gúrúji Ki Fatch.” A great quantity of cakes, made of wheat, butter, and sugar, are then placed before the volumes of the Sacred Writings, and covered with a cloth. These holy cakes, which are, in commemoration of the injunction of Navac, to eat, and give others to eat, next receive the salutation of the assembly, who then rise, and the Arabs[sic] pray aloud, while the musicians play. The Acales, when the prayers are finished, desire the council to be seated. They sit down, and the cakes being uncovered, are eaten by all classes of Sikhs. The Acales then exclaim, “Sirdirs (chiefs), this is a Gúrú-mátá,” on which prayers are again said aloud. The chiefs after this sit closer, and say to each other, “This sacred Grant’h, is betwixt us, let us swear by our Scriptures to forget all internal disputes and to be united.” This moment of religious fervour and ardent patriotism is taken to reconcile all animosities. They then proceed to consider the danger with which they are threatened, to settle the best plans for adverting it, and to choose the generals who are to lead their Dal-Khalsa, or army of the State, against the common enemy.

Sarbat KhalsaBy Kanwar Singh Dhillon. artofpunjab.com

The principal chiefs of the Sikhs are all descended from Hindoo tribes[sic]. The lower classes are protected from tyranny and violence by the precepts of their common religion, and by the condition of their country, which enables them to abandon, whenever they choose, a leader whom they dislike; and the distance of a few miles places them under the protection of his rival or enemy. It is from this cause that the lowest Sikh horseman usually assumes a very independent style, and the highest chief treats his military followers with attention and conciliation. The character of the Sikhs, or rather Sinhs[sic] ─which is the name by which the followers of Gúrú-Govind,, who are all devoted to arms, is distinguished─ is very marked. They have in general, the Hindoo cast of countenance, somewhat altered by their long beards, and are quite as active as the Mahratas, and much more robust, from their living fuller, and enjoying a better and colder climate. Their courage, which is equal to all times to that of any native of India, when wrought upon by prejudice or religion, is quite desperate.

The Sikh nation, who have throughout their early history always appear, like a suppressed flame, to rise into higher splendour from every attempt to crush them,

become, while they are oppressed, as formidable for their union as for their determined valour and unconquerable spirit of resistance; but a state of persecution and distress is the one most favourable for the action of a constitution like theirs. They are all horsemen, and have no infantry in their own country, except for the defence of their forts and villages, though they generally serve as infantry in foreign armies. They use swords, spears, matchlocks, and bows and arrows. They are bold and rather rough in their address, which appears more conspicuous to a stranger from their invariably speaking in a loud tone of voice. Talking aloud is so habitual to a Sikh, that he bawls a secret in your ear.

The Sikh soldier is generally speaking, brave, active, and cheerful, without polish, but neither destitute of sincerity or attachment, and if he often appears wanting in humanity, it is not so much to be attributed to his national character, as to the habits of a life which, from the condition of the society in which he is born, is generally passed in scenes of violence and rapine.

It would be difficult, if not impracticable, to ascertain the number of armies which the Sikhs could bring into action. They boast that they could raise more than a hundred thousand horse, and if it were possible to assemble every horseman, the statement might not be an exaggeration.

The Turbaned Man Turban Club